Felsenberg : Tasting and other Notes

As part of a long delayed visit to several wine estates in Rheinhessen and the Nahe in the early spring… Read more »

As part of a long delayed visit to several wine estates in Rheinhessen and the Nahe in the early spring… Read more »

The Eagle has landed. The code name for Apollo 11’s lunar module in 1969. Also the national bird of Germany. … Read more »

The crescent-shape strip of coastline between Ventimiglia and Livorno and the two large islands that mark the… Read more »

A 2017 post on this site called attention to Red Newt Cellars in New York’s Finger Lakes. When I… Read more »

If Weissburgunder (Pinot Blanc) is the newest Cinderella story in German white wine, its planted surface having tripled between 1995 and 2017, Silvaner is presently eclipsed. Germany’s most planted variety at the turn of the 20th Century, and third most planted as recently as 1995, Silvaner has gradually lost ground. The story is similar across the Rhine in Alsace, where Sylvaner (Alsace orthography) has now slipped from a 25% share of the region’s total vineyard to just 10%. In Austria, where the variety was born but may never have had much traction, planted surface has shrunk to fewer than 40 hectares countrywide. Still Silvaner is not endangered, remaining the second most-planted variety in Franken, and fourth most-planted in Rheinhessen. On these shores, it thrived in several California wine regions as early as the 1850s and as recently as the 1970s, often as part of a blend, or sold as Franken Riesling. These days it clings to a few tiny plots in the Santa Maria Valley and Sonoma. And one reported near Forest Grove in Oregon.

As a general matter it is far from clear what drives (and has driven) the ebb and flow of vogue around wine grape varieties over time. In Silvaner’s case, why did it lack traction in early modern Austria but still appeal enough to the abbot of Ebrach that he imported cuttings into Franken in 1665? Why was Silvaner more attractive to growers in Rhenish regions at the turn of the last century that at the beginning of the 21st?

Such questions deserve attention well beyond the scope of this post. Here I report instead my impressions from an opportunistic lineup of 17 Silvaners tasted at Stanford, CA on 3 March 2020. No effort was made to obtain wines from all areas where it is now important, or to reflect its relative importance by region. Or to identify and represent wines from “top producers.” What could be found easily was acquired, period. Happily, quite a few top producers were included. In the end 11 of the 17 wines came from German regions, 4 from Alsace and one each from California and the Alto Adige. Thanks are owed to several importers for their help, with special thanks to Tom Elliot of Northwest Wines, Ltd. for no fewer than seven wines from his Silvaner-rich list. A link to the tasting list is found at the end of this post.

My impressions from this tasting…

The List:

Rheinhessen Silvaner Alte Reben 2017 (Weingut Dr. Heyden)

Alsace Sylvaner Bollenberg 2014 (Domaine Valentin Zusslin)

Alsace “Les Vieilles Vignes de Sylvaner” 2017 (Domaine Ostertag)

Alsace Sylvaner 2018 (Domaine Charles Baur)

Franken Silvaner Retzstadter Langenberg Erste Lage 2017 (Rudolf May)

Rheinhessen Silvaner Saulheimer Probstey 2017 (Weingut Thoerle)

Suedtirol Eisacktal Sylvaner 2018 (Kuen Hof)

Rheinhessen Silvaner Feinherb 2017 (Weingut Strub)

Alsace Sylvaner 2017 (Albert Boxler)

Rheinhessen Silvaner Trocken 2018 (Weingut Wittmann)

California Sonoma Estate Sylvaner “Ode to Emil No. IX” 2018 (Scribe)

Franken Silvaner Iphoefer 2017 (Juliusspital)

Franken Silvaner Wuerzburger Stein 2016 (Juliusspital)

Franken Silvaner Escherndorfer Lump Erste Lage 2017 (Michael Froehlich)

Franken Silvaner Escherndorf am Lumpen “1655” GG 2016 (Michael Froehlich)

Franken Silvaner Retzstadter 2016 (Rudolf May)

Franken Silvaner Iphofer Julius-Echter-Berg GG 2015 (Hans Wirsching)

Although a short list of mostly small Riesling vineyards was reported to the Directory of Grape Growers of the Sonoma Viticultural District in 1891, the variety had barely a toehold in the landscape then, having lost ground after an early zenith in the 1850s. And sadly for Riesling, the variety’s lot in Sonoma has scarcely improved in the approximately 130 years since. The California Grape Acreage Report for 2019 found just 51 bearing acres in Sonoma County. Although specific acreage-by-variety data is not available for 1891, the long story short for Sonoma can scarcely be better than no-gain-no-loss.

Still, once in a while there is a flicker of good news about Riesling in Sonoma. Scribe Winery co-founders Andrew and Adam Mariani planted ca. two acres in 2007 about three miles east of the Sonoma Plaza, from which they make a small quantity of a cult bottling of low alcohol, bone dry Riesling that I have (alas) never tasted. Now the newest Sonoma Riesling news known to me is a few acres in the Cougar Ridge part of the Jackson family’s 900-acre Alexander Mountain Estate Vineyard, originally planted in 1997. Circa 2010, a few acres of this vineyard were re-grafted to white scions, including Riesling. These acres are found about 1000 feet above sea level on a steep (average slope is 44 percent) southwest-facing slope. West winds that chase summer fog off the vineyard around mid-morning. The soil here is of volcanic origin, consisting of Yorkville series clay-loam and broken volcanic rock. The rootstock is 110R; the new scion material consists of FPS Riesling 01 (~Weis 21B) and FPS Riesling 29 (~CTPS 49.) The man behind an exciting, serious, dry Riesling wine from these vines beginning in 2016 is Fabian Krause, a Hochschule Geisenheim graduate who worked first at Weingut Fritz Allendorf in the Rheingau, and then at Chateau Lassègue in St. Emilion, before moving on to Jackson Family Wines in Sonoma County. (There is a story behind this apparently unusual odyssey: Lassègue, like Vérité in Sonoma, is a joint venture of two families – the Jacksons and the Seillans – and Krause is married to Pierre Seillan’s daughter Hélène, who has recently become her father’s right hand at Vérité.)

With ample experience in Germany’s most Riesling-intensive wine region, Krause adapted his approach to suit the Alexander Mountain site, picking (in 2016) in multiple passes across two weeks of elapsed time, maintaining excellent acidity in every pick. The fruit was pressed as whole clusters, minimizing contact with the air, before reversing course post-fermentation, when Krause’s winemaking shifts from reductive to oxidative. After fermentation, the new wine was kept on its full lees until bottling. The result in 2016 is a bright, taut wine of low pH (between 3.0 – 3.1), 7.4 grams of acid and just 3 grams of residual sugar, slightly dusty on the attack, then softly fruity and strongly herbal at mid-palate with highlights of fruit peel. There is ample texture on the back palate, and the wine is aromatically exciting. The 2017, from a significantly warmer vintage, was of necessity picked in a single pass on 3 September, and botrytis-affected fruit entirely removed before pressing. This vintage presents as a slightly more fruit-forward and citrus-y wine, with a less-articulated complement of herbs. Four g/L of residual sugar this time to offset a bit more acid (8 g/L); the impression is less tense than in 2016, but the wine remains firm and dry.

Neither vintage of Riesling, nor a very interesting 2016 Sauvignon Blanc Krause fashioned from a stand of head-pruned Sauvignon vines planted in the 1950s, has yet been released. Together they will be the first releases under a new brand called Zeitlos — which translates as “timeless” – sometime in 2020. Given the painfully short list of California Rieslings that are perennially serious, and the even shorter list of Riesling-centric California wine brands, plus Riesling’s doleful status in Sonoma – the most vinous of the state’s counties outside the Central Valley — the debut of JFW’s exciting and “timeless” whites cannot come too soon. Stay tuned!

Miguel Lepe explains that he makes Riesling for his eponymous label “because of Claiborne & Churchill.” Claiborne & Churchill (see Riesling Rediscovered, pp. 326-28) is the original aromatic white specialist among California producers, focused as early as 1983 on Riesling and Gewurztraminer. Lepe, born in Salinas, now the owner and winemaker at Lepe Cellars, interned there in 2009 while earning a degree in Wine and Viticulture from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo.

Lepe calls himself a “millenial Hispanic.” This is now the largest age cohort within the largest ethnic population segment in California. He is, however, by no means typical. He belongs to the first generation of his family to be college-educated. He had essentially zero experience with wine as a beverage – neither he nor his parents consumed much alcohol –when he chose vine growing as an elective to complete the requirements for an A. S. degree in Business Administration at Hartnell College in Salinas. To explain this choice, Lepe says simply that he “liked plants and gardening.” Out of the vineyard and into the cellar, he was gradually hooked; for him “the smell of wine fermenting” was mesmerizing. In 2009, A. S. degree in hand, Lepe transferred to Cal Poly’s program in Wine and Viticulture. In addition to Claiborne & Churchill he worked harvests and internships across a large swath of land, heading a few miles north to Justin in Paso Robles, south to Waters Edge Wineries in Rancho Cucamonga, and eventually farther south by almost 3000 miles to cool-climate-oriented Casas del Bosque in Chile’s Casablanca Valley. Drawn back to the area around his Salinas home in 2013, he was handed a full-time job at Figge Cellars on the strength of a single interview. In a remarkable turn of fate Peter Figge (1970-2017) then became Lepe’s boss and mentor, encouraging and enabling him to create his own brand in 2015, to be made side-by-side with Figge’s, in part of a business park recently remade as a wine ghetto in Marina, a sprawly seaside town tucked between what was Fort Ord and the artichokes of Castroville. Lepe’s 2015 and 2016 vintages consisted of just one ton each of five varieties: Chardonnay, Zinfandel, Petit Verdot, Syrah (for rosé) and Riesling, enough to make fifty cases of each. In 2017, production of each wine doubled to 100 cases of each, thanks in part to a successful Kickstarter campaign. More recently he has “teamed up with new Monterey vineyards” to help grow his fledgling business.

Lepe sources the grapes for his Riesling from Luis Zabala’s meticulously farmed vineyard in Arroyo Seco, just south of the pioneering plantings begun ca. 1971 at Ventana. The Riesling at Zabala was mostly planted in 2007, in the deep alluvial gravel typical of the area. To execute his take on Riesling, Lepe has created a pick and cellar protocol that seems simple at first blush, but is not. He likes Zabala qua site for its “very good acids,” by which he means acids that high enough and strong enough to handle his circumstances and preferences. The former include very small lots and barrels as fermentation vessels; the latter includes an affinity for some malolactic conversion; “personally,” he explains, “it’s better to start with more acid than not enough.” At the same time, Lepe is one of many Riesling makers around the world who prefer a dry wine persona overall, but still worry that the wine may turn out a bit too lean if it contains no residual sugar at all. Lepe trusts his palate to find the golden mean, which may vary from vintage to vintage. So his protocols are roughly as follows. First, he picks Riesling twice, once between 19 and 20 Brix for acid and structure, then again around 22 Brix for a bit more ripeness and fruit expression, the combination giving him a “broad sensory profile” — and two (rather than one) fermentation lots in each vintage. Two of anything creates a blending opportunity. He prefers whole-cluster pressing to pre-fermentation skin contact. He settles the juice overnight in a stainless steel tank before transferring it to “well used” barrels for fermentation. (Lepe notes that “well-used” barrels are all he can afford; a good thing in my view, since Riesling is too naturally flavorful to need makeup!) At this point, things get really interesting. He co-inoculates the settled juice with a combination of yeast (Assmanshausen) and malolactic bacteria. Although malolactic conversion was normal in Riesling a century ago, a natural concomitant of multi-year élevage in large wooden tanks, few makers encourage it today, and most block it completely. (There are notable exceptions, of course, e.g., Zind-Humbrecht and Peter-Jakob Kühn, see Riesling Rediscovered, pp. 188-90 and 199-200.) For Lepe, ML is an important part of his toolkit. While the Assmanshausen ensures a strong (and relatively slow) fermentation capable of carrying the wine to full dryness, the ML bacteria transforms part (but not all) of the grapes’ sharp malic (apple) acid into softer lactic (milk) acid. But because Lepe also seeks to avoid the normal signatures of malolactic conversion — think butter and popcorn – he proactively starts and stops the malolactic conversion simultaneously with the primary fermentation. And he uses a strain of bacteria that does not produce diacetyl – diacetyl being the compound responsible for the aforementioned buttery aromas in most ML-converted whites. In 2018 Lepe added yet one more parameter to his protocol. He slowed the speed of the primary fermentation by moving the Riesling barrels to a temperature controlled space within the winery where he could set the ambient temperature at 45°F. The cooler temperature gives him more time to taste the unfinished wine and react, should he wish to arrest the primary fermentation before the last grams of sugar are turned into alcohol. Once dry (or stopped as the case may be) and racked, Lepe likes to leave the new wine on its fine lees for 4-5 months, to gain complexity and texture and to avoid any impression of “linearity,” and he generally stirs the lees once every two weeks. The twin fermentation lots generated by the two-picks protocol remain separate until about two months before bottling, when they are reunified. Sulfites are used parsimoniously, “just enough to keep things sound.”

With his fourth vintage now in the cellar, Lepe’s finished Rieslings have varied noticeably from one vintage to the next. My experience is limited at this point to the 2015 and 2016, both of which are current. The 2015 (tasted in 2018) is a good wine, fruit-forward, round at mid-palate, redolent of resinous herbs. It is not entirely dry, containing about 12.5 g/L of residual sugar. By contrast the 2016 Riesling is almost bone dry and (to my palate) very impressive. Pale straw in color, chamomile and lemon peel on the nose, citrus and pear on the palate, this is a taut, textured and long-to-finish wine with nice energy, intense flavors, and herbal accents of tarragon and summer savory. It is also extremely well priced at $22 per bottle. I look forward to tasting the 2017 when Lepe is ready to release it, and the 2018 in due season. The week after Christmas 2018, Lepe reported the 2018 still fermenting slowly, with about 8 g/L of sugar remaining. “I am aiming for as dry as I can,” Lepe wrote me, “but my decision will be based solely on taste.”

Lepe has attracted some attention for his unoaked Chardonnay, which has medaled in competitions, but the Riesling still flies a bit under the radar. For now, this suits Lepe quite well, giving him a product that can be sold in the tasting room he hopes to open sometime in 2019. For further information about Lepe Cellars, visit www.lepecellars.com.

Umbria, central Italy’s only landlocked regione, has a sub-prime reputation for very good wine. There is reasonable evidence that “traditional” Orvieto, made sweet, may have been exceptional in the 19th Century, but that reputation seems not to have survived the subsequent reinvention of Orvieto as a mass-market dry wine in the 20th. Recently, some observers have offered more positive assessments of Umbrian wine, pointing to vintners like Georgio Lungarotti and Arnaldo Caprai, who are deemed to have boosted regional standards in the final decades of the 20th Century. Here are a few notes from a visit to Umbria this autumn.

Umbria, like neighboring Lazio, is overwhelmingly white wine territory. Its most widely planted white grape variety is also Italy’s most planted white, known officially as Trebbiano Toscana. (This to the irritation of most Umbrians, by the way; Umbrians generally chafe when visitors situate them in Tuscany’s shadow.) This member of what is now called the “Trebbiano Group” is responsible for at least 60% of Orvieto, and is a component in white wines up and down the country’s peninsular length. Ian d’Agata’s excellent Native Wine Grapes of Italy (2014) helps to sort the confusion among Trebbiani: the various members of the “Group” are not clones of a single variety but distinct varieties with little in common save spurious nomenclature. For Umbria today, the good news is that Trebbiano Spoletino, another member of the Trebiano group but unrelated to Trebbiano Toscana, now attracts attention from local vintners, with good reason and results. This Trebbiano now appears to grow only in Umbria, especially between Spoleto and Montefalco, though it may or may not be genuinely autocthonous. It is far from ubiquitous, but single-variety Trebbiano Spoletino now shows up quite often on regional restaurant wine lists. Without seeking it out, I found it twice within a week. The first instance was Villa Mongalli’s “Calicanto” Trebbiano Spoletino Umbria IGT 2016, a crisp but voluminous wine handsomely built of citrus and herbs, vaguely reminiscent of Sauvignon Blanc without Sauvignon’s signature expression of methyoxypyrizines. Tank fermented and raised, the Calicanto comes from calcareous hills about 360 meters above sea level, between Bevagna and Montefalco. The second was two of the three white wines made by Antica Azienda Agricola Paolo Bea; the astonishing “Arboreus” Umbria Bianco IGT, which I tasted from the 2015, 2014, 2012 and 2011 vintages, and the nouveau-né “Lapideus” Umbria Bianco IGT, first made in the 2014 vintage. Both are, as far as anyone knows, “pure” Trebbiano Spoletino, the Arboreus from vines growing around 200 meters above sea level in the low hills between Montefalco and Trevi, while the Lapideus hails from 80 year old vines higher in the hills, closer to Pigge di Trevi. The 2015 Arboreus was savory and slightly nutty, like amontillado sherry, but also gritty, complete and kaleidoscopic. The 2014 was more about fruit peel and intensely aromatic, featuring lightly caramelized yellow fruits with giant complexity on the back palate. The 2012 showed orange- and tangerine-specific notes, as if citrus peel had been infused with verbena leaves to make an herbal tea. All these wines and the 2011 were made oxidatively, leaving the grapes to macerate on their skins for 22 to 36 days, and then leaving the new wine on the full lees for as long as 215 days! All are built with complex and dazzling structures from the extended skin- and lees-contact, while each remains memorably singular on its own. Astonishingly, all of Bea’s whites hover around 12° of alcohol; these wines are intricate and complex, and almost crowded with flavor, but not “big.” Like all Bea wines (see below for additional coverage), the fermentations depend entirely on naturally-occurring yeast and fermentation temperatures are not controlled.

Alongside Trebbiano Spoletino, Umbrian vintners are also working seriously now with Grechetto, though d’Agata makes clear that Grechetto is actually two unrelated varieties, so that even supposedly monovarietal instances may be cuvées in fact. Locals accuse Grechetto of being rustic, which is not unfair, but properly handled it can make quite serious and delicious wine: tense and mineral with hints of white flowers, citrus and apples, kept crisp with good acidity. My favorite during the October visit was from the Tili estate in Assisi: a 2015 Assisi Grechetto DOC. Two actually. The so-called “reserve” is made (exclusively?) for Enoteca Properzio, an wine store cum bar and restaurant in the heart of hill-perched Terni, while the straight version, less impressive and less overtly mineral, is an attractive “baby” version of the reserve — for about a quarter of its price.

On the red side of the Umbrian wine ledger, there is Sagrentino. As with many varieties believed native to Italy, its etymology, origins and original habitat are unknown, but there now seems to be more of it in Umbria than anywhere else. The variety is famous for its giant load of tannins and related polyphenols, and is slow and late to ripen, leading to wines that are often high in alcohol. But successful Sagrentino is also rich and flavorful – perhaps suggestive of what vintage-quality port could taste like if it were fermented to dryness rather than fortified to arrest fermentation. The aforementioned Arnaldo Caprai (Società Agricola Arnaldo Caprai) is often given credit for having reestablished Sagrentino’s reputation in the last quarter of the 20th Century, his Montefalco Sagrentino “25 Anni” bottling often cited as the best example of the genre. (See Bastianich, Grandi Vini [2010] for example.) The 2013 vintage of this wine, also tasted at Enoteca Properzio, was rich, smoky and enormous, with cigar-box aromas and, true to form, a very grippy finish. It had also been “internationalized” by élevage in new oak barrels.

As with Trebbiano Spoletino, however, the most exciting expression of the variety, at least on this trip, was chez Bea. Bea makes three dry reds entirely from Sagrantino, while two other reds are mostly Sangiovese signed with small percentages of Sagrentino. Like the Bea whites, the Sagrentini are methodologically very similar to each other; their differences reflecting terroir rather than technique. “Rosso de Veo” is made from the younger vines in the Cerrete vineyard, which sits atop the hills west of Montefalco, at an elevation of between 370 and 450 meters, in marl and limestone soils mixed with uplifted alluvia. Even at 15° and totally ripe, this wine is electric at its edges, showing brightly, the 2010 saturated with red fruit flavors accented with nuttiness. In exceptional years only, Bea makes a second Sagrantino from Cerrete, built from its older vines The 2009 Cerrete was lovely, like a great Vosne-Romanée: seamless, strong, graceful, and symphonic. When Cerrete is not made, a third Sagrantino is the estate’s flagship. This is Pagliaro, the name of another high elevation site, though a trifle lower than Cerrete. The 2010 vintage of this wine was deeply flavored and symphonic with impressions of moist earth and chocolate. Like the whites, all three Sagrentini feature exceptionally long vattings that extend well beyond the full length of the primary fermentation, before a first racking separates the new wine from grape skins and the heaviest detritus. This stage is followed by even more extended élevage, beginning with a year in stainless steel, then a year or more in large-format Slavonian oak tanks. A year or more in bottle before release is also normal.

Giampiero Bea is the man in charge at Azienda Paolo Bea since his father substantially retired. An architect by training, as is also his wife Francesca, Giampiero speaks slowly and respectfully about winegrowing that “assists nature,” wines “with the taste of the earth,” “technology that does not substitute for natural processes” and protocols that avoid “every artificial acceleration.” Although sentiments of this sort seem to fit in Umbria, where roads wider than two lanes are the exceptions, towns are small, and population is spread thin, the Beas and their wines are really viticultural and enological outliers, marching to a drummer of their own. Their Sagrantinos seem almost comparable: just more seamless, symphonic, convincing, compelling – and released later – than other serious examples made across the Valle Umbra. But Bea’s whites are something else entirely. No other Umbrian Trebbiano Spoletino or Grechetto is even recognizable alongside Santa Chiara, Arboreus or Lapideus. The latter may have a superficial similarity to so-called orange wines, or to late disgorged Champagne owing to their long contact with lees, but are singular in ways and to degrees that frustrate comparison, not only with other Umbrian whites, but with white wines of almost any provenance. They are sui generis. Singularity generally deserves applause in the wine world, especially as a contrast to the surfeit of homogenous wines in the marketplace. Still it can be hard to know what foods pair well with Bea’s wines. While not unfriendly to food, especially Umbrian specialties like Norcian corallina or freshly grated white truffles – Bea’s whites are objects of attention on their own, stealing oxygen from any comestible within reach. Nevermind. Try Bea’s Sagrentini and his whites anyway if you have not already, in Umbria or in the foreign markets into which eighty percent of production is sold. (In the USA, the importer is Neal Rosenthal, contact info@madrose.com for additional information.) Give the wines the concentration and attention they deserve, even if you need to sublimate truffles, salumi or some other comestible to make the necessary time and space.

Apart from Paolo Bea there is plenty of tasty product in local wines stores and restaurant lists, much of which scores high on price-performance. And Umbria is rather a good place to discover art, enjoy an Indian summer, pass the autumn equinox, celebrate uncrowded towns, and unwind.

Sometimes epiphanies come in pairs. In April of this year, on different days in different places, I happened to taste two American dry Rieslings of vastly more than routine interest. Each pushes the dry Riesling envelope in a distinctive way, with surprising results that I report here.

Stirm Los Alamos Valley Riesling Kick-On Ranch “eøølian” 2016

A special lot of Riesling from the Kick-On Ranch in Santa Barbara’s Los Alamos Valley; see Riesling Rediscovered, p. 333-335 for details on the vineyard. Ryan Stirm of Stirm Wine Company, about whom more is found in an earlier post on this site (http://oenosite.com/is-a-riesling-renaissance-beginning-in-california-chapter-1-ryan-stirm/), enjoys pushing vinous envelopes of many kinds. In 2016 he elected to experiment with a zero-sulfur protocol for part of the fruit he takes from Kick-On, dubbing it Kick-On “eøølian.” Half of this lot was sold in kegs to high-end on-premise establishments where keg wines by the glass have good visibility. Visibility aside, kegs can be advantageous when sulfur has been excluded from winemaking; not only are keg wine sold through quickly, but inert gas automatically replaces wine as the latter is removed, avoiding oxidization. The rest of the lot was bottled conventionally. My notes: Aromas of lemon and straw. A cornucopia of citrus, pear, apple and melon flavors on the palate is punctuated with sabers of minerality. A combination of malolactic conversion, long lees contact and abundant (ripe) acid creates rich texture, tension and a long bone-dry finish. This wine is persistently exciting from first sniff to last drop. 11.4°! Note that Stirm’s “classic” vatting from Kick-On in the same vintage is also excellent. Without the eøølian for comparison, the classic cuvee would have been impressive enough. In comparison, however the eøølian soared, showing exceptional purity, precision and jump-from-the-glass excitement. My notes on the classic cuvee follow: Macerated yellow flowers and yellow plum buttressed with citrus pith and a tense structure, and delicious, and a friendly 12.9°. Chalk up a goo example for the folks who have often said that “natural” wines display a brilliance lacking in their sulfured siblings.

Weinbau Paetra Eola-Amity Hills Riesling “Elwedritsche” 2016

This wine has nothing in common with the Stirm except that it is exciting, and pushes the envelope for dry Riesling. This is an Eola-Amity Riesling dubbed “Elwedritsche.” The grapes come from Methven Family Vineyards at the northeast corner of the AVA, whose cellar also happens to be home to Weinbau Paetra, the creation of Bill Hooper and his family. Hooper personally farms for Methven the vine rows used for Elwedritsche and other Rieslings; he insists on this, so that he can grow grapes as he wants them for his wines. (Elwedritsch, for the curious, is the name for a possibly mythical, possibly extinct gallinaceous bird said to inhabit [or to have inhabited] woods on the east flank of the Haardt Mountains in the German Palatinate, just north of Alsace. There is even a museum dedicated to this creature in Speyer, a historic city on the Rhine in the Palatinate.) Hooper learned winemaking not far from this habitat, at Fachschule für Weinbau und Oenologie in Neustadt an der Weinstrasse, between 2009 and 2012. While a handful (or two) of Americans have studied at Geisenheim over the years, Germany’s highest-profile wine school and research center, Hooper is one of only two to have completed the entire curriculum at Neustadt, including associated apprenticeships, one of which was worked with the talented Andreas Schumann, the mind behind Weingut Odinstal (http://oenosite.com/wachenheims-secret-vineyard-odinstal/). How an American from the upper Midwest was launched on this trajectory — which took him through wine retailing in Minnesota to a special interest in Riesling, then to a German girlfriend who became his wife, then to Germany for the aforementioned studies, and finally to Oregon — is too long a story to tell here, where the point is Elwedritsche-the wine. There were only 88 cases of this wine made in 2016, but it is a tour de force. It begins with a deep, rich nose of yellow stone fruits, especially apricot. The palate is intense and concentrated, laced with spicy fruit, ginger and mint, and it tastes clean, with no bitterness, though it makes a poly-phenolic impression. It is also intentionally evocative of the Palatinate (Pfalz) – dry and stone-fruit-driven as these wines typically present — but with an exceptionally powerful personality. The must macerated on the skins for 24 hours before fermentation, which is long by Pfälzisch standards; thereafter there was neither added yeast, nor enzymes, nor fining agents of any kind, and only modest additions of sulfur. Although the alcohol is modest at 13°, acidity substantial at 7.5 g/L, and residual sugar low at just 4g/L, this is a powerful wine, to be savored, discussed and remembered, but perhaps paired cautiously with food. It is also a bold indicator that very serious Riesling has been grown and made at Weinbau Paetra since 2014. Volumes are tiny, quality high and prices very reasonable. ‘Nuf said. (http://www.paetrawine.com)

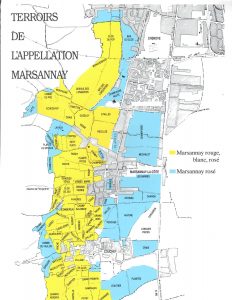

For a visitor, Marsannay presents today much like other wine communes in the Côte d’Or. The village core is small, covering less surface than a single block in midtown Manhattan. A church and partially shaded benches mark the main place. A modern and generously-appointed municipal complex stands out among older and lesser structures. Signage directs visitors to the cellars of Marsannay’s dozen-plus vignerons, most within a short walk of the village core. The distribution of vineyards is much like other communes too. The best climats are found just upslope of the Route des Grands Crus between the 300 and 400 meter contours, facing predominantly east, and form a nearly continuous ribbon more or less unbroken by fallow land or scrub; lesser sites sit below the Route on flatter and loamier terrain that is shared with other crops and buildings. As elsewhere in the Côte d’Or, Pinot Noir is the sole red tenant in Marsannay’s vineyards, and Chardonnay the main variety among whites.

Marsannay, however, is a special case. It lies just nine kilometers from the Palais des Ducs in Dijon, and barely maintains any degree of separation from Dijon’s seemingly limitless sprawl. Its population has quintupled since 1950, a majority of which is now either retired or works in Dijon, a fact that helps explain the village’s hefty investment in municipal services. The sprawl has also imperiled vineyards, driving Marcenacien vignerons to fight suburbanization, sometimes successfully.

A century ago, however, a different relationship with Dijon changed Marsannay fundamentally, separating its fortunes from the rest of the Côte d’Or and impacting its viticulture in ways that continue to be felt. After mostly prosperous centuries as the capital of the Duchy of Burgundy, and additional centuries of rule by French kings and a regional parlement, Dijon changed vocations after the Revolution. A large urban proletariat replaced erstwhile aristocrats and bureaucrats, creating interalia a new, intense and persistent demand for very ordinary wine. Apparently recognizing an opportunity, Marsannay’s vignerons (and their neighbors at Couchey and Chenôve) uprooted the Pinot Noir that had made the Côte d’Or famous, but yielded parsimoniously, and scrambled to plant more prolific varieties that were well suited to mass market wines, mostly Gamay and Aligoté.

In the 1820s some Marsannay vineyards had figured on lists compiled by André Jullien and Denis Morelot, the first godfathers of vineyard classification in the Côte d’Or. But by 1855 Jules Lavalle, another godfather of the classification, was able to find only a few vineyards anywhere in the Côte Dijonnaise where Pinot was still the main tenant, effectively removing Marsannay and its neighbors from the laborious work that would culminate, by the 1930s, in the ensemble of Burgundy’s controlled appellation arrangements. Phylloxera in the 1870s compounded the impact of the shift to Gamay and Aligoté. Now focused on cheap wine and high margins, Marcenacien vignerons were reluctant to replant after phylloxera struck their vines. Marsannay and its neighbors then missed yet another opportunity to rejoin the mainstream of Côte d’Or activity in the 1920s. Now finally willing to restore Pinot Noir in lieu of Gamay and Aligoté, they dedicated nearly all of their crop to rosé. So it came to pass in the 1930s, when the Burgundian AOCs, including village appellations and cru designations, were created, that no village appellation was approved north of Fixin, nor was any climat north of Fixin accorded cru status.

Today the Marsannay story is all about revival, and quality that is comparable to the rest of the Côte de Nuits. The deep roots of this revival can be traced back to the same to the same “dark” days in the 1920s that has deepened its problems. The bright light was the marriage of one Josef Clair (1889-1971) to Marguerite Daü. Clair replanted Marguerite’s inheritance to eliminate the damage caused by phylloxera, and privileged Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in the process. He also founded Domaine Clair-Daü, the first widely respected estate at Marsannay since the middle of the 19th Century. But the estate’s reputation depended more on its holding outside Marsannay, and most of its replantings of Pinot Noir within the commune went to make rosé.

Not until the 1970s and 1980s was there a serious revivial within Marsannay proper, led by a cohort of native sons and exogenous vintners To some degree this cohort was catalyzed by the liquidation of Clair-Daü. The liquidation literally forced Bruno Clair, Josef Clair’s grandson, to set himself up de novo with his part of the sundered estate. Another piece of the estate passed to Monique Bart; this is now the core of Domaine Bart, ably exploited by Monique’s son Martin and nephew Pierre. Other Marcenacien winemakers also rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s, notably Sylvain Pataille, Laurent Fournier (Domaine Jean Fournier) and Philippe Huguenot (Huguenot Père et Fils). Signs of seriousness were widespread. Pataille was a trained enologist before creating his estate; Bruno Clair hired a full-time enologist so that he could devote the lion’s share of his personal attention to the vines rather than the cellar. Again there was an elbow effect from the proximity of Marsannay to Dijon: to prevent good vineyard land from falling victim to shopping centers and suburban housing, the Marcenacien vintners were forced to make common cause. The same sense of common cause was then deployed in support of a shift from simple rosé back to serious red wines from historically superior sites. This embrace of red wines as the commune’s crown jewels, and the steady increase in the planted surface devoted to red wine production, were key factors in the INAO’s 1987 approval of a Marsannay AOC including parts of Chenôve and Couchey – enfin.

Now young Marcenacien vintners have launched the commune’s most ambitious quest yet: to secure 1er Cru status for the AOC’s best lieux-dits. With the help of geologists who worked to align geological maps of the area with the boundaries of lieux-dits, a proposal was first agreed locally, then refined in collaboration with regional authorities, and finally sent forward to the national INAO. The current proposal, under discussion in one form or another since ca. 2008, asks 1er Cru status for 14 of 78 lieux-dits within in the AOC.

The northernmost of the 14 sites is the Clos du Roy, which had once belonged to the Dukes of Burgundy but passed to the French crown at the end of the 15th Century. As befits a site named for royalty, Clos du Roy gives especially handsome, elegant wines. The coolest site is said to be Les Echézots, sometimes spelled Es Chezot, which straddles a hill between two combes, basking in downdrafts from both. Echézots gives wines with a somewhat softer elegance than those from Clos du Roy; Echézots’ tannins seem to be wrapped in velvet. The smallest sites are Saint-Jacques and Clos de Jeu, southwest of the village core, and the southernmost is Champ Perdrix, in Couchey. The total surface occupied by the 14 sites amounts to 174 hectares, or roughly 58 percent of the approximately 300 hectares currently approved for the production of red wines within the Marsannay AOC.

Herein lies both ambition and problem. Nearly everyone with responsibility for the reputation of Burgundy’s wines realizes that Marsannay was shortchanged in the 1930s. But vineyard classifications being political as well as scientific, too much change too quickly is not possible. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that, as it stands, the proposal would give Marsannay, in a single stroke, the greatest concentration of 1er Cru Pinot Noir vineyards of any commune in the Côte d’Or which is without Grands Crus. More than neighboring Fixin where 1er Cru vineyards occupy just 19 percent of the surface planted to red grapes. More than Savigny-les-Beaune where the 1er Cru share of the total red surface is 43 percent. Higher even than Nuits-St-Georges, where the analogous number is 45 percent.

Marcenacien vintners being realists, the current bet among them (based on informal conversations I had at this year’s Grands Jours de Bourgogne) is roughly as follows: First, the INAO will approve 1er Cru status for much less than the 174 hectares in the current proposal, probably sometime in the next two or so years. Second, while a few lieux-dits will be approved in their entirety, others will be approved in part only, especially those which are known to contain some land that is too low on the slope or too loamy for top-quality wines. Third, some lieux-dits not approved in whole or in part when the first promotions re announced may still be promoted later. These are bets only. Time will tell.

Although the reclassification saga will likely continue to make headlines, especially when the deed is done, the real story about Marsannay is the persistent increase, year after year, in the number of very good single site wines. Many such wines have already developed enviable reputations. Jérôme Galeyrand has turned heads with his Combe du Pré bottling since 2011. Bruno Clair’s Marsannay flagship, from Les Longeroies, is regarded as sure value-for-money, while his 2014 edition of Les Grasses Têtes, shown at this year’s Grands Jours, was fine and elegant. Also at the Grands Jours, Fougeray de Beauclair’s Les St-Jacques was beautiful and blackberry-inflected; Hervé Charlopin’s 2016 Langerois long and fluid, while Régis Bouvier’s 2016 Longerois was also long but especially rich and velvety.

Despite the press of business associated with the Grands Jours, Martin Bart made time to taste with me in his cellar. Few producers, I would argue, have been more comprehensively serious about their single site wines than Bart. In 2013, the estate, made single site wines from each of nine different lieux-dits: seven climats in Marsannay itself plus Clos du Roy in Chenôve and Champs Salomon in Couchey. Martin does not pretend that all of these are candidates for 1er Cru. Certainly not Les Finottes, a diminutive triangular parcel on nearly flat land composed mostly of deep sand, which gives a lovely, savory and herb-inflected wine that Martin describes as the estate’s “entrée de gamme” among the single site bottlings. It has been made separately since since it became a monopole of the estate simply because it is distinctive, not because it pretends in any way to greatness. It is also worth noting that Domaine Bart cleaves generally to vineyard and cellar practices that showcase the differences among neighboring terroirs. Enlightened farming creates healthier vines in self-sustaining ecosystems. Then, in the cellar, many parameters are terroir-revealing. Sane and appropriate combinations of pre-fermentation cold soaks with fermentation temperatures that begin around 18° C, naturally occurring yeasts, restrained use of pump-overs and pigeage, all help to avoid excessive extraction, which can be terroir-obscuring. The parsimonious use of new oak barrels, rarely more than 25 percent, mixed with older barrels, demi-muids and stainless tanks, helps too, especially for sites in Marsannay which tend generally toward understated, mid-weight wines that open politely but not voluptuously.

When 1er Cru is appended to the names some Marsannay climats in the years ahead, Marcenacien vignerons will have every reason to celebrate. With many of the wines from these lieux-dits already showing praiseworthy excellence, one is perhaps allowed to hope that the new imprimatur, when it comes, will be allowed to lie lightly on Marcenacien labels. Will prices for the newly designated 1er crus rise? Officially, the answer is negative since prices for these wines as site-designated village wine are already higher than village wines without site designations, but in the end supply and demand will rule. On verra.